Explore the connections

between climate and…

More climate webpages coming soon!

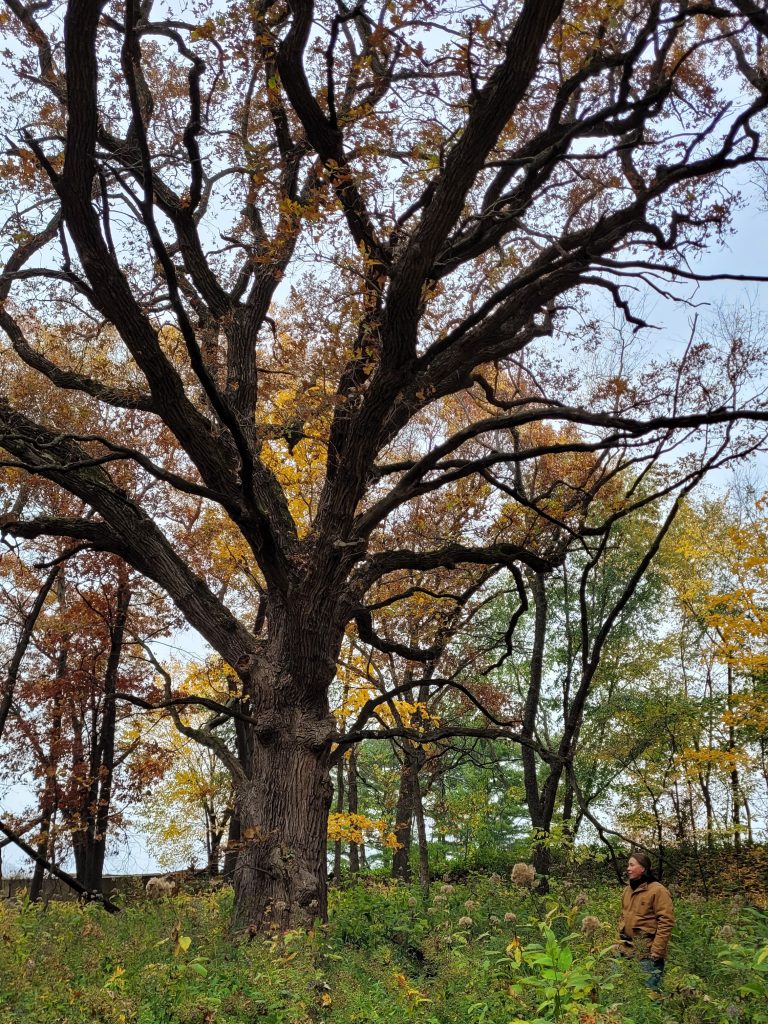

Do you have a favorite individual tree in your woods? Maybe it’s a tall, rugged bur oak that you climbed as a kid, or a wide, dependable sugar maple that you’ve tapped for decades. But does that tree have any offspring growing in the understory? If not, the future of your woodland will look very different from the past and present.

Wisconsin’s forests face a variety of challenges when it comes to growing new generations of trees. By learning how the changing climate is affecting tree reproduction, you can give seeds, seedlings, and saplings a better chance at growing into the next cherished trees in your woods.

Jump to section

What is changing with tree regeneration in Wisconsin?

Regeneration is the process of trees reproducing in a woodland. Regeneration can happen naturally when mature trees spread seeds, sprouts, or suckers that grow into young trees. It can also happen artificially when you plant trees or seeds. Since trees don’t live forever, regeneration is crucial for the long-term health of a forest.

Many Wisconsin woodlands don’t have as much regeneration now as they did in the past. And even in woodlands with lots of regeneration, a few species tend to be overrepresented among baby trees: red maple, sugar maple, ironwood (hophornbeam), and black cherry. Meanwhile, trees that don’t like shade, such as oak, pine, and hickory, are underrepresented among baby trees. If we don’t take steps to change the situation, our forests will become less diverse and thus less resilient to extreme weather, pests and diseases, and other stresses.

Sugar maple

Overrepresented among baby trees

Ironwood

Overrepresented among baby trees

Black cherry

Overrepresented among baby trees

White oak

Underrepresented among baby trees

Red pine

Underrepresented among baby trees

Shagbark hickory

Underrepresented among baby trees

So what’s causing the problem? Several things.

Deer browse: Imagine having a fancy lawnmower that chops grass down to the ground but leaves clover unaffected. Soon, your lawn would be covered in clover and hardly any grass would be left. Deer have a similar effect on trees and shrubs. They prefer eating trees like white cedar, hemlock, oak, pine, birch and maple, and they avoid eating ironwood, black cherry, and invasive shrubs like buckthorn and Japanese barberry. The plants that deer leave alone tend to fill more of the forest than the plants that deer munch on. Deer populations are increasing in many parts of Wisconsin, so deer browse is a bigger problem than it used to be.

Invasive earthworms: Earthworms are great for composting and gardening, but they harm Wisconsin forests and are not native here. Earthworms can deplete soil of nutrients, change the fungi and invertebrate communities, and completely consume the leaf litter and duff layers. These are the layers that sugar maple seeds prefer to grow in, so earthworms make it hard for baby sugar maples to thrive. Earthworms also tend to compact the soil, which causes it to dry out faster and precipitation to run off, exacerbating the effects of drought and extreme rainfall.

Worse droughts: As the climate continues to change, we’re seeing longer and more severe droughts in many Wisconsin counties than in the past. Droughts stress all ages of trees, but young trees that don’t yet have extensive root systems are especially vulnerable.

Invasive understory plants: As invasive plants spread through a forest, their dense vegetation takes over the understory, out-competing native plants for light, water, and nutrients. For example, buckthorn can create too much shade for native tree seedlings to grow, and garlic mustard can harm the beneficial fungi in the root systems of maples, oaks, pines, birches, aspens, and others. Learn more about the impacts of invasive plants, how to manage them, and how the changing climate is affecting them.

Lack of fire: Historically, fire played an important role in many Wisconsin forests. Jack pines are adapted to fire as a part of their reproduction process, and fire can also stimulate the growth of young oaks. White pine, red pine, white spruce, black spruce, hemlock, birch, and aspen can also benefit from exposed mineral soil created by a fire. After centuries of fire suppression, many forests that experienced frequent fire now struggle to grow the next generation of trees.

The importance of refugia

It’s tempting to think in terms of “climate winners” and “climate losers”—but things aren’t that simple. Some vulnerable species, like paper birch, have deep cultural significance for tribal communities. Vulnerable tree species also have very important ecological benefits in Wisconsin forests, so we may want to do whatever we can to help them survive. One way to do that is to select small refugia: areas like ravines, kettles, and north-facing slopes where temperatures may not rise as quickly. In those refugia, you can protect vulnerable species that are declining on the rest of your land.

When deciding how to manage your woods for climate resilience, it’s important to remember that you’re not starting with a clean slate. Start by figuring out which species are common as mature trees on your land and which are common as young trees on your land. Then check the vulnerability of these species in your region of Wisconsin. You might decide that instead of trying to encourage species that are barely present, your best path forward is to support the species that are already common there—even if most of them are listed as vulnerable.

How to improve tree regeneration

The lack of tree regeneration has many causes—but on the flip side, that means it has many solutions. Keep reading to learn about strategies that you can use to benefit the next generation of trees on your land. Then, we encourage you to talk with a forester for tailored advice about which of these strategies are best suited for your situation.

Leave legacy trees and deadwood

Think about your favorite big tree in your woods. This might be a good candidate for a legacy tree: a tree that you intentionally never harvest so that it grows old and dies. Due to their large size, legacy trees often produce lots of seeds, so they can help with natural regeneration. Legacy trees are also an important feature of old-growth forests.

When a legacy tree dies while standing, it becomes a snag, a standing dead tree. Snags provide excellent wildlife habitat. When they fall to the ground as deadwood, they gradually return nutrients to the soil and often become nurse logs where seedlings soon emerge. Eastern hemlock, northern white-cedar, and yellow birch grow especially well from nurse logs.

Leaving legacy trees isn’t the only way to create snags and deadwood. You can also intentionally girdle a living tree to turn it into a snag, or you can cut down and leave a tree to create deadwood. The ideal densities of legacy trees, snags, and deadwood for forest regeneration depend on the forest type. The table below shows recommended numbers for three example forest types.

| Forest type | Legacy trees per acre | Snags per acre | Downed logs per acre |

|---|---|---|---|

| Northern hardwood (sugar maple, yellow birch, basswood, white ash, beech, hemlock) | 12–20 | 8–12 | 8–20 |

| Oak-central hardwood (oak, hickory, elm, black cherry, red maple, white ash, green ash, basswood, hackberry, sugar maple) | 4–18 | 4–7 | 3–14 |

| Spruce-fir (balsam fir, white spruce) | 10–35 | 7–12 | 8–17 |

Values shown are for trees/snags/logs at least 20 inches in diameter. Note: This information was adapted from a New England management guidebook. However, the 3 selected New England forest types share a lot in common ecologically with our Wisconsin forest types.

Despite all the benefits of snags and deadwood, they do have trade-offs. Snags can catch fire easily, which complicates prescribed fire planning and can increase wildfire risk. Also, snags near buildings or trails can pose a safety risk. That’s why we recommend using the above guidelines as a starting point for a conversation with a Wisconsin forester about how snags and deadwood relate to all your goals for your woodland.

Choose silvicultural practices with regeneration in mind

Silviculture refers to a broad range of practices that can guide how your woods grow and change over time. Here are several common silvicultural activities that you can use to increase the chances that seedlings and saplings will grow into mature trees.

Crop tree release involves removing the trees that are competing with your desired trees for canopy space. First, you pick the “crop trees” whose growth and health you want to focus on. If your goal is regeneration, it’s good to pick legacy trees for some of your crop trees. For each crop tree, you then cut down some of the trees whose canopies are touching the canopy of your crop tree. “Releasing” the crop trees in this way provides canopy space for them to grow out, and it creates open areas for young trees to grow. Before trying crop tree release on your own, we recommend watching our webinar on choosing which trees to harvest, reading this detailed guide, and getting advice from a forester.

Scarification exposes bare mineral soil to make it easier for species like oak, pine and birch seeds to start growing. For small-scale scarification, you can use a fire rake, agricultural drag harrow, or similar tools. For larger-scale scarification, forest managers use a small-wheeled tractor with disk, bulldozer with a blade, a skidder, or other machinery. Scarification is done either shortly before or shortly after a harvest, depending on the forest type, equipment available, and how much slash material will be created by the harvest.

Invasive plant management helps reduce the amount of competition that your desired native seedlings face. If you succeed at managing buckthorn, bush honeysuckle, and other invasive plants that could otherwise take over the understory, tree seedlings will have more sunlight, water, and nutrients—giving them a better shot at growing to maturity. Invasive plant management typically takes several years and requires a combination of techniques, such as hand-pulling, mowing, prescribed fire, and/or herbicide treatments.

Some of the same techniques used to control invasive plants can also help with native plants that may compete with desired tree regeneration. For example, it’s often important to manage young aspen, red maple, or hazelnuts if you are conducting an oak or pine regeneration project. These tree and brush species tend to grow fast and can shade out or take nutrients away from your desired regeneration.

You can create canopy openings or gaps by removing selected mature trees to create better light conditions for tree seedlings. This mimics natural disturbances like windthrow or mature trees dying from old age. In Wisconsin, canopy gaps are most often used in northern hardwood forest types. Canopy gaps can range in size from 0.1 to 2 acres. Generally, smaller gap sizes favor shade-tolerant species like sugar maple or beech, whereas larger gaps favor intermediate to shade-intolerant species like yellow birch or northern red oak. If you want to create canopy gaps, pick spots that already have some seedlings present, and leave some mature trees near the gaps to maintain a seed source. Also, make sure to watch for brush and non-native plants inside the gaps so that you can remove them if needed.

Click the arrows on the graphic below to explore how creating canopy gaps can improve old-growth characteristics in northern hardwood forests.

Collect tree seeds

When people want to plant trees, those seeds have to come from somewhere—so you can collect seeds to plant on your own land or to sell for other landowners’ use!

The best way to harvest and process seeds depends on the species. Some should be collected while still on the trees, while others should be collected from the ground. In general, cones are ready to collect when they are mature but still closed—they disperse their seeds when they open. Acorns are generally good to collect after recently falling from oak trees during a mast year (when oaks are producing a bumper crop of acorns)—but be sure to check the viability of acorns with a float test. After collecting seeds, clean off any debris and store seeds in a cool, dry location. If you are selling them, deliver them to the buyer as soon as possible.

As of 2025, the Wisconsin DNR Reforestation Program purchases 19 species of tree seeds in August and September, including sugar maple, oak, pine, spruce, tamarack, and more. Staff at DNR nurseries grow the seeds into seedlings, which they sell to public and private landowners across the state.

Only collect tree seeds from trees growing in your woods, not from landscaping trees in your yard or other cultivated trees. If you plan to sell tree seeds, make sure to talk with the buyer before you start collecting so that you understand all of their guidelines.

Plant trees

If the conditions aren’t right for natural regeneration alone to produce enough young trees, you can embark on a planting project. Begin by figuring out the characteristics of the soil, how water moves and drains on the site, and how much sunlight will reach the new trees. Then, pick several appropriate species to plant, not just one—that diversity will make your forest more resilient.

Planted trees need a lot of care to survive. You may need to mulch and/or water them, you’ll likely need to manage competing vegetation, and you’ll definitely need to be proactive to prevent deer from munching on them. Make sure you have a plan for maintenance before you start planting. We recommend filling out the DNR’s personalized tree planting plan, too.

Protect young trees from deer

Whether you’ve planted them or they’ve emerged on their own, your young trees are vulnerable to deer browsing. You can protect them in several ways, each of which has pros and cons in terms of money and labor.

Fencing that surrounds the entire planting is often best for the health of the woods because it protects both trees and understory plants from deer. To protect individual trees, you can use tubes or cages (or, for conifers, caps on the main buds). Deer repellant sprays are another option, but you’ll likely need to reapply them during the growing season. If you conduct a timber harvest, you can create a slash wall out of slash and low-value tree tops as another way to keep deer out.

In combination with the above strategies, you can hunt the deer in your woods (or invite others to do so) to reduce their population.

Further Reading

DNR Reforestation Division

- Reforestation Homepage

- Personalized Tree Planting Plan

- Ordering Trees and Shrubs

- Become a DNR tree seed collector

- Creating a Forest: A Step-By-Step Guide to Planting & Maintaining Trees

University of Massachusetts Extension Forestry

Northern Institute of Applied Climate Science (NIACS)

UMN Extension Forestry

UW–Madison Extension

- Next Step Video – How to Choose Which Trees to Harvest and Which to Leave

- Proper Tree Planting Techniques

- 5 Steps to Plant a Tree

University of Tennessee Extension Forestry

My Wisconsin Woods

Keith Phelps

Working Lands Forestry Educator

keith.phelps@wisc.edu

920-840-7504

Page last updated January 2026.

Additional photo credits:

- Black cherry: Bill Cook, Michigan State University, Bugwood.org

- White oak: Paul Wray, Iowa State University, Bugwood.org

- Red pine: Paul Wray, Iowa State University, Bugwood.org