Wisconsin’s forests have a complex relationship with fire. Although out-of-control wildfires can be disastrous, most of Wisconsin’s land—including many forests—used to experience regular fires that kept ecosystems healthy and in balance. Depending on the landscape, the frequency of fire ranged from almost every year to every 20 years or so. The loss of this good fire has left many of our forests weakened and less resilient to the many challenges they face today.

Informed by that history, we can use fire intentionally to benefit ecosystem health while protecting the safety of the land, water, soil, plants, animals, people, and infrastructure. Prescribed fire is like a medicine for the forest—although its short-term effects can seem unpleasant, it’s a necessary step toward healing.

Jump to section

What is prescribed fire?

Prescribed fire is the intentional use of fire to achieve land management goals. It is also the continuation of a long history of fire in our region.

Prior to European settlement, Indigenous communities used fire to steward the land for thousands of years, and fires sparked by lightning also shaped the landscape. But fire suppression policies in the 1800s and 1900s caused a cascade of unintended consequences. Now, policies and practices are moving back toward promoting prescribed fire or “good fire.”

When used in the right context, prescribed fire has many benefits:

- It reduces hazardous fuel loads, making future wildfires less dangerous to the ecosystem, people, and property.

- It helps the next generation of fire-adapted trees like oaks and pines to grow.

- It helps understory plants that need disturbances and open tree canopies to survive.

- It creates forest mosaics, helping to break up middle-aged forests into a variety of landscapes.

- It can kill and slow the growth of invasive plants that are not adapted to fire.

- It creates better foraging and breeding habitat for many animals.

- It creates snags (standing dead trees) where wildlife can nest.

- It helps nutrients cycle through the soil.

Read more about the common benefits of prescribed fire in this overview from the Wisconsin Prescribed Fire Council.

Which types of Wisconsin forests can benefit from prescribed fire?

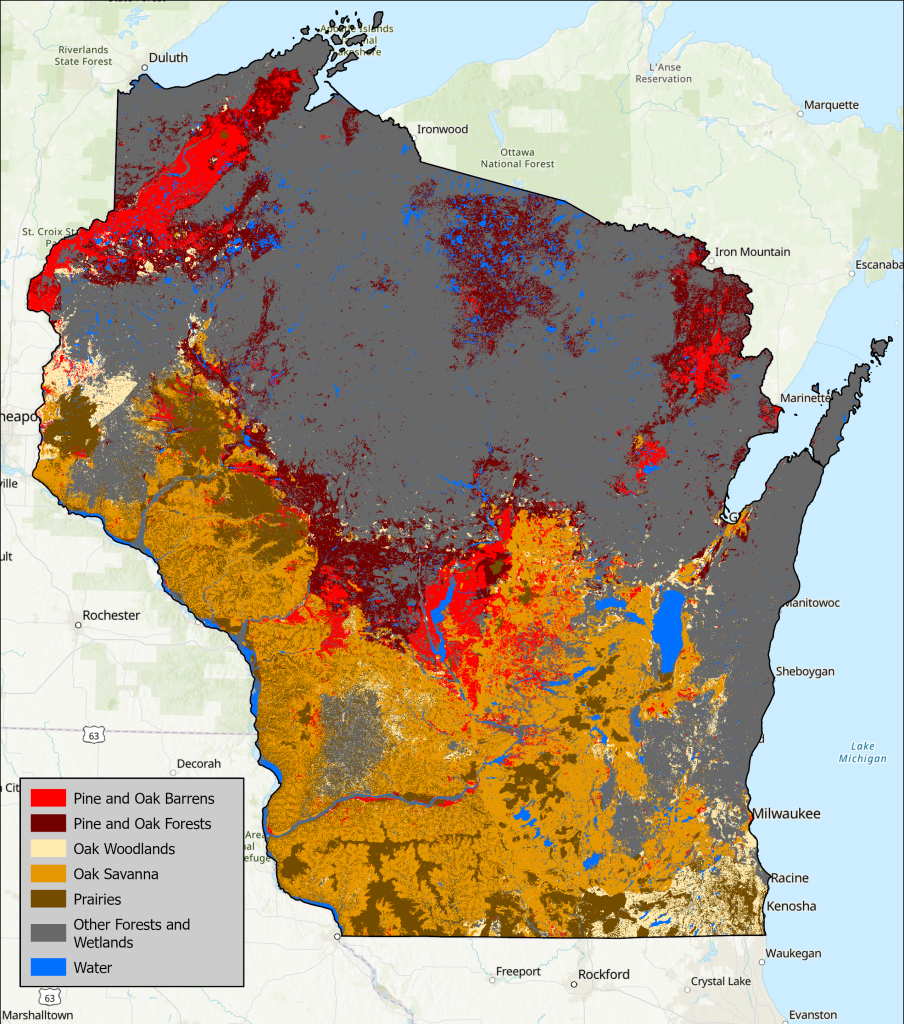

Fire is one of many types of ecological disturbances, or forces that influence the age and structure of a forest. Not all Wisconsin forests are adapted to frequent fire. For example, northern hardwood forests (dominated by maples, beech and basswood) can thrive without fire. However, many forests in Wisconsin are fire-dependent, meaning they need frequent low-intensity fires to maintain their ecological health.

Scroll through the following fire-dependent Wisconsin forest communities to see how prescribed fire can help these forests stay healthy and resilient, including a sampling of the specific plants and animals that benefit from fire. Note that the ideal frequency of fire in your woods today might differ from the historical frequency of fire because of the different challenges facing today’s forests.

To learn more about non-forested Wisconsin plant communities that are adapted to fire, read these fact sheets on wetlands and tallgrass prairies.

Pine and oak barrens

In pine and oak barrens, the most common trees are jack pine, black oak, northern pin oak, and occasionally red pine. Barrens have lots of open space, with trees scattered individually, in small groups, or in dense groves. Often, most of the trees are around the same age because fire triggered the growth of the next generation of trees. Barrens historically experienced fire every 6-12 years.

Jack pine sometimes has cones that cannot open without heat. When that is the case, fire is crucial for its seeds to get out of the cones and have any chance of growing. Even when the cones open without heat, the seeds depend on exposed mineral soil, which can be created by fire.

Pine and oak barrens provide vital habitat for many rare animals and plants. Sharp-tailed grouse depend on large open areas such as those in recently burned barrens, and Kirtland’s warblers only breed in large forests of young jack pine. Often found in sunny openings such as those created by fire, lupine is the only food for the caterpillars of the endangered Karner blue butterfly.

Pine and oak forests

The most common trees in Wisconsin’s pine and oak forests are white pine, red pine, jack pine, white oak, red oak, and black oak. Red maple, black cherry, paper birch and aspen are also sometimes part of the mix. The understories typically are not very diverse because many of these forests are plantations, but depending on where you are in the state, you might find huckleberries, blueberries, bracken ferns, wood anemones, starflowers, and Pennsylvania sedge. Naturally occurring pine relicts and old-growth forests tend to be more diverse in understory plants.

Pine-oak forests historically experienced fire every 6-12 years. Fire removes the organic layer at the top of the soil, exposing the mineral soil that red and white pine seeds need to start growing.

Lowbush blueberry (which is tasty for humans and wildlife alike) can be found in a variety of oak and pine landscapes. A prescribed fire will kill the aboveground portion of a blueberry bush and stimulate growth in the underground portion. The year of a fire, the bush won’t produce fruit, but for the next few years after that, it tends to offer a bountiful harvest of blueberries. Black bears eat blueberries, and a good blueberry year makes bears less likely to eat crops, beehives, or livestock.

Oak woodlands

Oak woodlands in Wisconsin usually feature white and bur oak. Red oak, black oak, and shagbark hickory are also common. In healthy oak woodlands, somewhere between 40% and 65% of the ground is in the shade at noon.

In the past, fires would pass through oak woodlands every 1 to 5 years. Oaks are well-adapted to resist fire: mature oaks have thicker bark than other hardwood trees, young oaks can resprout after a fire kills their aboveground growth, and acorns sprout underground where they are protected from fire.

When an oak woodland doesn’t have frequent enough fire, it gradually becomes a closed-canopy forest with shade-tolerant trees like sugar maple and basswood. Shade-intolerant trees like oaks struggle to survive and reproduce in these conditions. Prescribed fire gives oaks an advantage over competing plants, prepares the soil for the growth of new trees, and helps manage invasive plants.

Oak savannas

Oak savannas are similar to oak woodlands, but more open and prairie-like. Oak savannas have 1 to 17 trees per acre, and only 5% to 40% of the ground is shaded at noon. Bur oak, white oak, chinquapin oak, black oak, and shagbark hickory are the most common trees.

Like oak woodlands, oak savannas historically experienced fire every 1 to 5 years. Fire plays a key role in keeping a savanna open and not dominated by woody brush, creating habitat for a multitude of prairie plants and animals. After a burn, big bluestem grows more vigorously and leadplant sends up extra sprouts. As a result, they produce more flowers than they would in an unburned area.

The ornate box turtle, which is endangered in Wisconsin, provides an example of the nuances involved in planning prescribed fires. These turtles need grass or prairie areas, so they benefit in the long term from burns. But if they get caught aboveground during a fire, they can die. Timing prescribed burns to happen while ornate box turtles are hibernating underground protects them from the flames.

What is changing with fire in Wisconsin?

Changes in the climate, fire policies, and people’s behaviors are all influencing the present and future of fire in Wisconsin’s forests.

Wildfire

In the coming decades, wildfires will likely become more frequent, burn more acres, and last longer. Many aspects of the changing climate contribute to this. Less winter snowpack, more frequent and severe droughts, and earlier springs all cause plants and the duff layer of the soil (fungi and decomposing material below the leaf litter) to dry out more quickly, increasing the risk of fire. Warmer weather also increases fire risk.

Just like forests across the continent, Wisconsin’s forests are still dealing with the legacy of centuries of fire suppression. Without the low-intensity fires that used to be common in many types of forests, fuel has built up on the forest floor, and plants that are sensitive to fire have replaced fire-adapted plants. So when a wildfire does happen, it is often more damaging than it would have been in the past.

We’re already beginning to see these effects. In 2025, fueled by dry conditions and the lack of snow, Wisconsin had a record number of wildfires in January and February, earlier than the typical wildfire season.

But we’re not destined to have a future full of devastating forest fires. Prescribed fire and other sustainable management strategies can reduce the chances of a wildfire running out of control. And 98% of wildfires in Wisconsin are sparked by people, most often through debris burning—meaning that responsible behavior can make unwanted fires much less likely. Learn how to prevent fires from debris burning, equipment issues, campfires, and other causes.

Prescribed fire

Foresters, landowners, and conversation organizations increasingly recognize the importance of prescribed fire to make forests healthier and more resilient. According to one estimate, prescribed burns now occur on around 50,000 acres each year in Wisconsin. However, the state has around 4.5 million acres of fire-dependent ecosystems that could benefit from burning, meaning we would ideally be burning around 1 million acres each year. (These figures include prairies and other fire-dependent habitats in addition to forests.)

It’s not yet clear how the changing climate will affect land stewards’ ability to use prescribed fire. People who do prescribed burns are noticing that planning burns is becoming harder because conditions in the spring and fall are less predictable than in the past. However, in some cases, warmer and drier conditions could expand the window of time when safe and effective burning is possible.

What is clear is that when applied appropriately, prescribed fire offers many benefits to make our forests more resilient to invasive plants, extreme weather, and other stresses.

Who can help me do a prescribed fire?

Conducting a safe and effective prescribed fire requires a lot of expertise. Fortunately, there are several ways you can connect with experts and keep learning.

One great organization to connect with is the Wisconsin Prescribed Fire Council. If you want to chat about your options, meet other people in the prescribed fire world, and learn about training opportunities, you can reach out to Training Specialist Kristina Weld. With enough time and dedication, you can eventually go from knowing nothing to being a certified burn boss!

Another resource is your local DNR forester (or your private consulting forester if you already have one). They will be able to give you individualized advice about when and how your land might benefit from prescribed fire.

If you know that your woods could benefit from fire but don’t have the skills to do it yourself, you can hire a contractor to plan and carry out the burn. Check out the Wisconsin Prescribed Fire Council’s member organizations to find a contractor. The Wisconsin DNR also maintains a list of restoration contractors, many of whom do prescribed burns.*

One way to team up with other landowners is through a prescribed burn association: a group of landowners in a certain geographic area who help each other do burns by sharing equipment, expertise, and/or crew members. Wisconsin has a few of these, but there isn’t yet a searchable database. If you want to start a prescribed burn association, check out Missouri’s list for examples of how they work, watch this webinar from the Wisconsin Forestry Center, and consider coordinating your efforts with the Wisconsin Prescribed Fire Council.

*Lists provided for informational purposes only and do not represent Extension’s endorsement of any particular company.

Further reading

- Prescribed fire overview (Wisconsin DNR)

- Prescribed fire overview (My Wisconsin Woods)

- Prescribed Burning in Forest Management in the Upper Great Lakes (Ruffed Grouse Society)

- Growing the ‘Good Fire’ (Wisconsin DNR)

- Restoring Fire to Wisconsin’s Native Landscapes (The Nature Conservancy)

- Brochures on the role of prescribed fire in Wisconsin’s wetlands, tallgrass prairies, oak savannas, and oak woodlands (PDF) (Wisconsin Prescribed Fire Council)

- Bulletin #6: Prescribed Fire (Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts) (PDF)

- Wisconsin Fire Needs Assessment (Wisconsin Prescribed Fire Council)

- Understanding Historical Fire Regimes to Foster Resilient Forests (talk by Jed Meunier, Wisconsin DNR)

- Prescribed Fire for Forest Management webinar series (Wisconsin Forestry Center)

- Wisconsin Prescribed Fire Tracker Dashboard (Wisconsin DNR)

- Wisconsin Burn Permits (Wisconsin DNR)

- Prescribed Burn Go-No Go Checklist (Wisconsin Prescribed Fire Council) (PDF)

- Prescribed Fire Basics (Oregon State University Extension) (Note: burn laws are different in the Pacific Northwest than in Wisconsin, so make sure to check Wisconsin regulations, too)

- Guidebook for Prescribed Burning in the Southern Region (University of Georgia Extension) (Note: burn laws are different in the South than in Wisconsin, so make sure to check Wisconsin regulations, too)

- Map of prescribed burn associations in the United States

- Firewise Landscaping (UW–Madison Extension) (PDF)

If you have questions about prescribed fire in your woods or feedback on this webpage, contact:

Keith Phelps

Working Lands Forestry Educator

keith.phelps@wisc.edu

920-840-7504

Page last updated January 2026.