Emerald ash borer (EAB) is a non-native invasive beetle that kills ash trees by eating the tissues beneath the bark. It first arrived in Wisconsin in 2008, and by 2024 it had been detected in all 72 counties. EAB typically kills more than 99% of the black, white, and green ash trees in a forest. There’s no sugarcoating it—these losses can be devastating. But with proactive forest management, you can make your woods more resilient and guide the ecosystem towards a healthy future even with fewer ash trees on the landscape. You can also join efforts to collect seeds and find ash trees that may be resistant to EAB.

If you aren’t yet familiar with EAB or the ash species native to Wisconsin, check out these identification resources:

Jump to section

Because emerald ash borer is a relatively new threat to our forests, much remains uncertain about its long-term impacts, which management approaches will be most successful in the long term, and which tree species to plant to replace ash. The recommendations here are based on the best available evidence, but they could change in the future as researchers continue studying EAB and land managers continue testing different approaches in forests across North America.

Impacts of emerald ash borer in Wisconsin

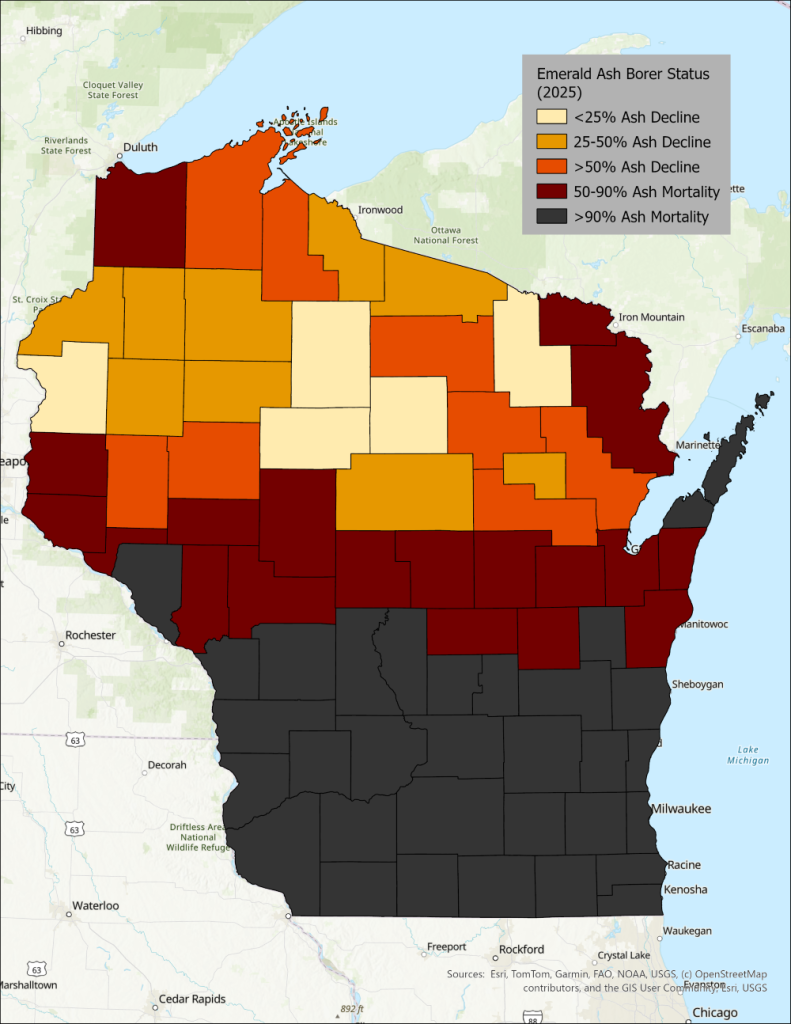

Emerald ash borer has already killed more than 90% of the ash trees in the southern third of Wisconsin. It isn’t yet as widespread in the Northwoods, where in some counties less than 25% of the ash population is in decline so far. However, northern Wisconsin has more than half of the state’s ash trees, so the effects of EAB are already a major issue there.

As adults fly from tree to tree, EAB spreads slowly, around ½ mile to 4 miles per year. Firewood infested with larvae can also spread EAB, which is why it’s important to never transport firewood more than 10 miles. Very cold temperatures can kill EAB larvae, which hunker down under ash bark for the winter. But as our winters continue to warm, EAB will likely be able to spread more quickly through northern Wisconsin.

The effects of EAB are especially worrying in northern lowland forests such as black ash hardwood swamps, where black ash is one of the main tree species present. Living black ash trees uptake an incredible amount of water, so when the ash die, water tables can rise and create swamping conditions. In areas with high ash cover, one possible outcome is that cattails, sedges, grasses, and non-local invasive plants then take advantage of the extra light and water, causing the ecosystem to transition into a non-forested wetland. In recent years, extra stressors like droughts, extreme rainfall, changes in seasonality of flooding, and cottony ash psyllid (another non-local insect) have put even more stress on black ash trees in northern Wisconsin, making them potentially more vulnerable to EAB.

How to manage affected and threatened forests

Whether emerald ash borer is already decimating your woods or has yet to arrive, taking action as soon as possible will give your woods the best chance of a healthy future. The first step is to assess the situation in your woods. Here are several things to look for.

- Species, sizes, and ages: How prevalent are ash trees? What other species are present? What sizes and ages are present for each species?

- Future generations of trees: How many ash and non-ash seedlings and saplings are present? How are other plants and deer affecting the growth of young trees?

- How water moves: Is your land low-lying and swampy, upland and dry, or in between? Where is the water table, and how quickly or slowly does the soil drain?

- Distance to EAB infestations: How far away is the closest known EAB infestation?

The answers to these questions, along with your overall goals for your land, will help you decide whether to harvest ash trees, when to do so, and which ones to harvest. They will also inform which species of trees you’ll encourage to grow instead and how to give them the best chance at success.

The following sections give some management strategies you can consider based on whether you have upland or lowland ash stands. See the Wisconsin DNR’s EAB silviculture guidebook for more detailed guidance, and make sure to talk with a forester to help you decide on what to do. We also recommend contacting your local DNR forest health specialist for regionally specific EAB advice.

Upland stands

Typically, upland stands with ash are found in northern hardwood forest types, which also commonly have sugar maple, yellow birch, basswood, beech, and/or hemlock. In these forests, white ash is the most common ash species, and usually less than 20% of the trees are ash. Generally speaking, managing EAB impacts in upland stands is easier than in lowland stands because the upland stands often have a wider range of non-ash species and less wet soils.

As a first step, make sure to monitor for and manage invasive plants. EAB creates open areas in the forest canopy, which invasive plants can exploit to outcompete desired non-ash seedlings and saplings. Continue invasive plant management regardless of any other next steps to ensure invasive plants stay in balance with native ones.

As a rule of thumb, if your stand has 20% or less of ash (or at least 40 healthy non-ash trees per acre), the stand likely has enough non-ash trees to keep the site forested once EAB moves through. In that scenario, you can manage for the remaining trees in the stand and leave behind some ash for ecological benefits, such as seed production or serving as a source of snags (standing dead trees) for wildlife habitat. What’s more, the gaps and extra sunlight left behind by the declining ash can encourage regeneration of other tree species in the forest (if you keep invasive plants at bay). You can also use sustainable timber harvesting to salvage some ash or create additional canopy gaps for non-ash tree regeneration.

If your stand has more than 20% ash (or less than 40 healthy non-ash trees per acre), you may need to take a more active approach to maintain forest cover of non-ash trees. Typically, this means creating canopy gaps to favor the growth of young non-ash trees. You’ll probably notice ash regenerating in your canopy gaps since young ash trees do well with more sunlight— and that’s ok! Although EAB affects young ash too (even branches less than 1 inch in diameter can get infested), retaining some future generations of ash trees provides genetic diversity for researchers’ efforts to identify EAB-resistant trees. However, if more than 10% of your seedlings and saplings in the gaps are ash, you may want to consider cutting or treating the young ash with herbicide to help other tree species along, since white ash typically grows faster and can shade out other species.

Whether ash is common or not in the stand, aim to have many tree species regenerating, not just one or two. In some cases, this may mean planting young trees to improve species diversity and increase the number of young trees growing.

Lowland stands

Managing EAB impacts in lowland stands dominated by black or green ash is challenging. You have to consider how water moves on the site, a limited number of tree species that can tolerate wet soils, and equipment accessibility issues. The unique characteristics of your woods will influence how the ecosystem responds to EAB, other stressors, and the management actions that you take. In these wet forest stands, it’s important to follow forestry best management practices to protect water quality and sensitive soils.

Due to these complexities, we highly recommend that you consult with a forester who can help you evaluate a lowland ash stand (see Appendix A in the DNR’s EAB silviculture guidelines) and determine next steps based on your goals. If your forest is a low-quality site (say a mucky stand with cattails, few trees, and frequent flooding), you may find that guiding its transition to a non-forested wetland community may be worth considering.

Just like in an upland stand, as a first step make sure to monitor for and manage invasive plants. Declining ash trees allow for more sunlight for wetland invasive plants such as reed canary grass or phragmites to grow. Keep in mind that if you are considering applying herbicides in a wetland or swamp, you may need a pesticide applicator license.

Sustainable timber harvesting can help promote the growth of young trees from a wide range of non-ash species. However, operators typically need frozen ground days to prevent soil rutting and other environmental damage in lowland stands. Across Wisconsin, we are seeing a decline in the number of frozen ground days, making sustainable harvesting in lowland stands more economically and ecologically challenging.

If your stand has 20% or less of ash (or at least 40 healthy non-ash trees per acre), the stand likely has enough non-ash trees to keep the forest as forest once EAB moves through. In this case, you can manage for the remaining trees in the stand and encourage the regeneration of those non-ash tree species. Salvage harvesting can occur, but it’s a good idea to balance different management objectives. For example, leaving some dead ash as snags benefits wildlife habitat. In addition, leaving some mature declining ash (especially female trees that produce seeds) can help future conservation efforts for the species. Who knows—you may find one or two of them survive as lingering ash, and the seeds from those individuals are especially important for researchers!

If your stand has 20% or more of ash (or less than 40 healthy non-ash trees per acre), using sustainable timber harvesting to promote regeneration of non-ash trees may be an option. Several different harvesting methods are recommended for regenerating non-ash species in lowland stands. The site, tree species present, timber volume, and other factors influence a forester’s decision of which harvesting method to use. On the other hand, a forester may determine that timber harvesting is not feasible on your site given its challenges. That’s why it’s best to have a conversation with your local forester about regenerating non-ash trees in lowland areas.

Whether ash is common or not in the stand, you can also plant non-ash trees to replace dying or dead trees. Keep reading to learn more about planting young trees to replace ash.

Planting trees in affected forests

As is common with many woodlands in Wisconsin, you may find that your tree regeneration is inadequate or has low species diversity. Retaining future tree cover through direct planting is a great option to improve your woodland’s resilience so that it provides clean air, clean water, and wildlife habitat long into the future. You can plant before or after EAB appears in a stand. Keep scrolling to explore some possible tree replacements in upland and lowland ash stands.

Options for upland trees

| Species | Shade tolerance | WI climate change vulnerability | Preferred soil type | Likelihood of being browsed by deer | Drought tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White Pine | Medium | Medium-low | Sandy/loamy | High | Medium |

| White Oak | Medium | Low | Mesic loam, well drained | High | Medium-high |

| Northern Red Oak | Medium | Medium-low | Variable | High | Medium |

| Red Maple | Medium | Low | Variable | Medium | Medium |

| Black Cherry | Low-medium | Low | Loamy, well drained | Low | Medium |

| Yellow Birch | Medium | High | Loamy, well drained | Very high | Low-medium |

| Sugar Maple | High | Medium | Mesic loam, well drained | Medium | Low-medium |

Note: Data in this table come from Tree Planting to Enrich, Restore, and Adapt Northern Forests and the Climate Change Field Guide for Northern and Southern Wisconsin Forests. These options generally apply for northern hardwood forest types to replace white ash. Remember that maintaining some white ash in the forest helps ensure the species is still present, as we can never replace its cultural and ecological benefits!

Options for lowland trees

| Species | Shade tolerance | WI climate change vulnerability | Preferred soil type | Likelihood of being browsed by deer | Flooding tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swamp White Oak | Medium | Medium-low | Clay, loam, floodplain | High | High |

| Red Maple | Medium | Low | Variable | Medium | Medium-high |

| Silver Maple | Medium | Low | Alluvial, floodplain | Medium | High |

| White Pine | Medium | Medium-low | Sandy/loamy | High | Low-medium |

| Tamarack | Low | Low | Organic (wet, bogs) | Low-medium | High |

| Cottonwood | Low | Low | Sandy/silty, floodplain | Medium-high | High |

| Yellow Birch | Medium | High | Loamy, well drained | High | Low-medium |

| American Elm (disease-resistant) | Medium | Low | Variable | Medium | High |

| Northern White-Cedar | High | High | Calcerous, organic (wet, bogs) | High | Medium-high |

| Hackberry | Medium | Low | Calcerous, clay-loam, well drained | Low | Low-medium |

| Black Willow | Low | Low | Alluvial | High | High |

| Paper Birch | Low | High | Sandy-silty loam | Medium-high | Medium |

| River Birch | Low | Low-medium | Alluvial, sandy | Low-medium | High |

Note: Data in this table come from Tree Planting to Enrich, Restore, and Adapt Northern Forests, the Climate Change Field Guides for Northern and Southern Wisconsin Forests, and the Wisconsin EAB Silviculture Guidelines. These options generally apply for northern and southern hardwood forest types to replace black and green ash. Remember that maintaining some black and green ash in the forest helps ensure these species are still present, as we can never replace their cultural and ecological benefits!

Planting tips

- Talk with a forester for site-specific recommendations on which tree species to plant.

- Manage invasive plants before planting, before creating canopy gaps, and throughout a planting project.

- Before and after planting, manage weedy brush, grass, and other vegetation that may overtop and shade out your young trees.

- Have some form of deer browse protection for young trees (tree tubes, bud caps, fencing, etc.).

- Recommended tree density varies by site, but 500 to 900 trees per acre is a good starting point.

- In lowlands, plant in hummocks (elevated mound areas) that may be less susceptible to flooding.

Other efforts to protect ash trees

Researchers, land managers, Tribal communities, and others are still working tirelessly to preserve the ecological and cultural legacy of ash trees in our state and across North America. Although our forests will never look the same as they did before the arrival of emerald ash borer, these ongoing efforts could help ash return to the landscape in the future.

One management strategy that has worked for other invasive species is to find a biological control: another creature that harms the problematic species. In the case of EAB, four species of parasitoid wasps have shown potential to reduce EAB populations. Scientists have released these wasps into the wild since 2007, including at many locations in Wisconsin. They won’t eliminate EAB, but they could give more ash trees the chance to mature and reproduce. Researchers are also testing fungi as potential biological controls.

Another positive sign is that some lingering ash survive EAB infestations. These trees may have genetic traits that help them resist the beetle, so researchers are hoping to use them to breed more EAB-resistant ash trees. The Wisconsin DNR and UW–Madison are developing ways to find lingering ash through aerial surveys, and you can look for them as you walk through your woods. If you have an ash tree on your land that has survived when the rest have died, you can report it to the Great Lakes Basin Forest Health Collaborative. With your permission, they might come harvest seeds or take a cutting to grow in a greenhouse.

Lastly, the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission, the Ash Protection Collaboration Across Waponahkik, Wisconsin DNR foresters, and other groups are collecting ash seeds both to help with breeding and to store for future plantings. Black ash trees are especially important beings for traditional basket making for many Tribal communities in the Midwest and Northeast U.S., and tree seed collection efforts are one way to preserve the cultural practice of basket making.

If you are interested in collecting ash seeds for breeding purposes, ask your forester about how to get involved in these efforts.

Further reading

- Emerald ash borer overview (WI DNR)

- Emerald Ash Borer Silviculture Guidelines (WI DNR, 2018)

- WI DNR Forest Health Specialist contact page

- Emerald ash borer fact sheet (WI DNR, 2023)

- Emerald Ash Borer Information Network

- 10 Recommendations for Managing Ash (Forest Stewards Guild, 2020) (PDF)

- Ash Seed Collection and Regeneration (Ash Protection Collaboration Across Waponahkik)

- Managing Ash Woodlands: Recommendations for Minnesota Woodland Owners (UMN Extension, 2019)

- Managing Northeastern Forests Threatened by Emerald Ash Borer (University of Massachusetts Extension, 2025) (PDF)

- Trees in Peril (The Nature Conservancy, 2024)

If you have questions about emerald ash borer and your woodland, or feedback on this webpage, contact:

Keith Phelps

Working Lands Forestry Educator

keith.phelps@wisc.edu

920-840-7504

Written by Keith Phelps and Scott Hershberger (UW–Madison Extension) and reviewed by Martha Sample (University of Minnesota and Northern Institute of Applied Climate Science). Page last updated February 2026.