Explore the connections

between climate and…

More climate webpages coming soon!

No matter whether you’ve owned your woodland property for one year or 50, you probably hope your woods will remain healthy and resilient for future generations. Unfortunately, invasive plants are increasingly harming Wisconsin’s forests. In the coming years, non-local plants may spread even more due to changing climate conditions—it’s like your woods are a sports team, and the rules of the game are changing. By understanding the links between the changing climate and invasive plants, you’ll be able to be a better coach of your forest team and get the rogue players off the field.

Jump to section

If you’re just starting to learn about invasive plants, also check out our webpages about why invasive plants are a problem and how to manage them.

How climate trends benefit invasive plants

The same characteristics that make certain species invasive in the first place, like being adaptable to different habitats and growing quickly, often make them better able to cope with changing climate conditions than native species. Here are some of the ways that changing climate conditions can benefit invasive plants. But keep in mind that each species will respond differently—a change that benefits one invasive plant might hurt another invasive plant.

Longer growing seasons enable some invasive plants to extend the window of time when they are growing and native plants are not. Compared to native plants, some non-native plants are better able to get a jump-start on spring leaf-out in response to warm temperatures.

Warmer temperatures allow some invasive plants to expand their range northward. Some invasive plants struggle to survive very cold winters. As winters become milder, invasive plants common in the southern U.S. may appear for the first time in Wisconsin, and those found in southern Wisconsin may spread to the northern part of the state.

The higher level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere acts as a fertilizer to invasive plants, causing more vigorous growth. Many native plants can’t take advantage of the extra carbon dioxide as effectively as some invasive plants can.

Droughts decrease the effectiveness of some herbicide treatments. In hot and dry conditions, plants tend to grow a thicker cuticle (waxy coating) on their leaves, and sprayed herbicides evaporate more quickly. Both of these changes make it harder for foliar herbicide treatments to get inside the target plants.

Events that stress or kill native plants create the opportunity for invasive plants to get a foothold. When trees and understory plants are weakened by prolonged drought, severe floods, wildfires, or pests and pathogens, they are less competitive against invasive species. And when a cluster of trees dies unexpectedly, opening up a gap in the canopy, invasive plants can rapidly spring up to take advantage of the extra light reaching the ground.

Despite these broad trends, not all invasive plants will benefit equally from climate change, and some will even decline. More research is needed to get a better sense of how the changing climate will affect specific invasive species. But here are a few examples of what scientists expect to happen.

Japanese barberry benefits from warmer temperatures throughout its range, so it is predicted to expand northward and become more common in its existing range.

Round leaf bittersweet benefits from milder winters, so it is predicted to expand northward but not to become more common in its existing range.

Glossy buckthorn benefits from milder winters but doesn’t thrive in droughts and hot summers, so both the northern and southern boundaries of its range are predicted to shift northward.

Garlic mustard doesn’t thrive in droughts and hot summers, so it is predicted to become less common.

Whether a particular plant thrives in your woods depends not just on climate conditions, but also on the local context—the other plant and animal species already present, the history of the land, and the soil composition all matter. We can’t be 100% certain what the future will look like, but we can be confident that non-local plants will continue to cause problems in Wisconsin woodlands. And many of the solutions remain the same, too: proactively monitor for new arrivals, use a variety of management methods, and learn from other landowners and natural resource professionals.

New invasive plants to look out for

Because of warmer temperatures, many invasive plants are creeping northward. Below are some examples of species that are currently not found (or rarely found) in Wisconsin but may soon be here. By keeping an eye out for them—and reporting them if you see them—you and other woodland stewards will be able to get a head start on managing them when they arrive.

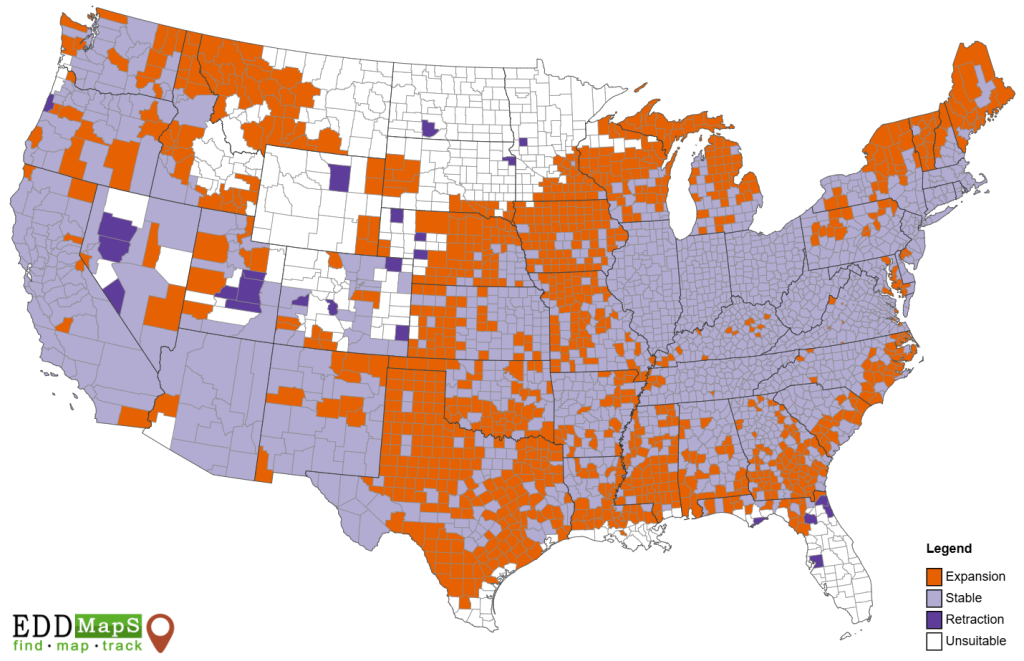

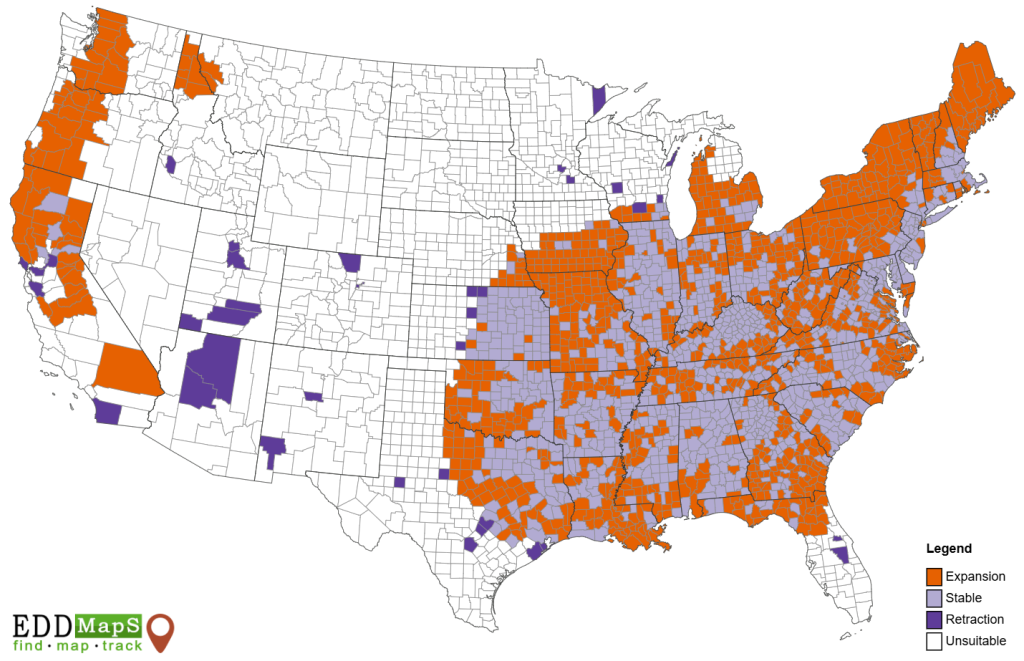

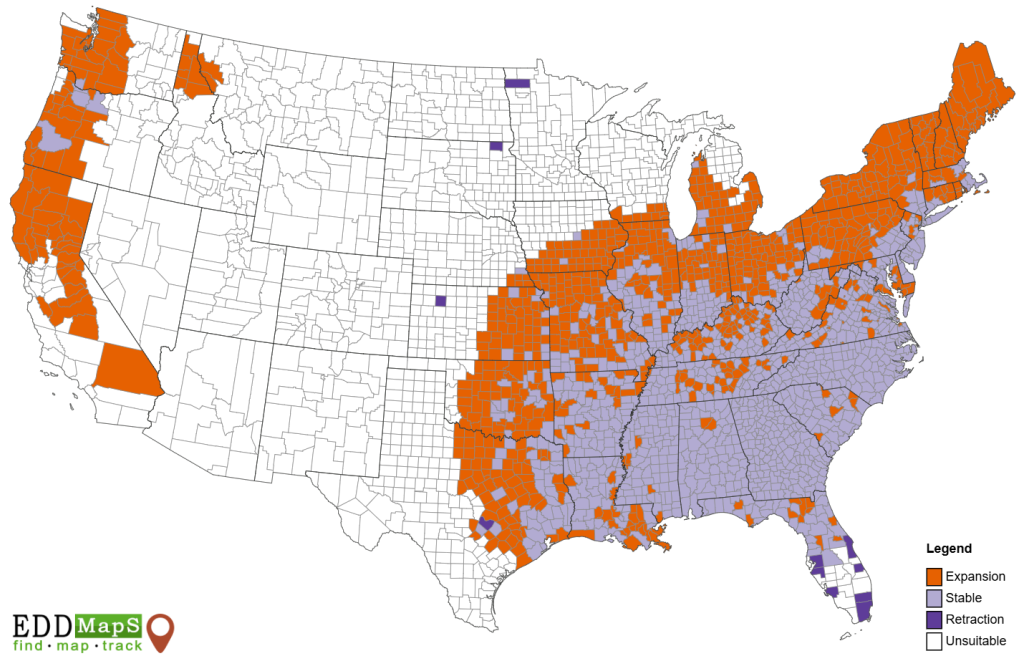

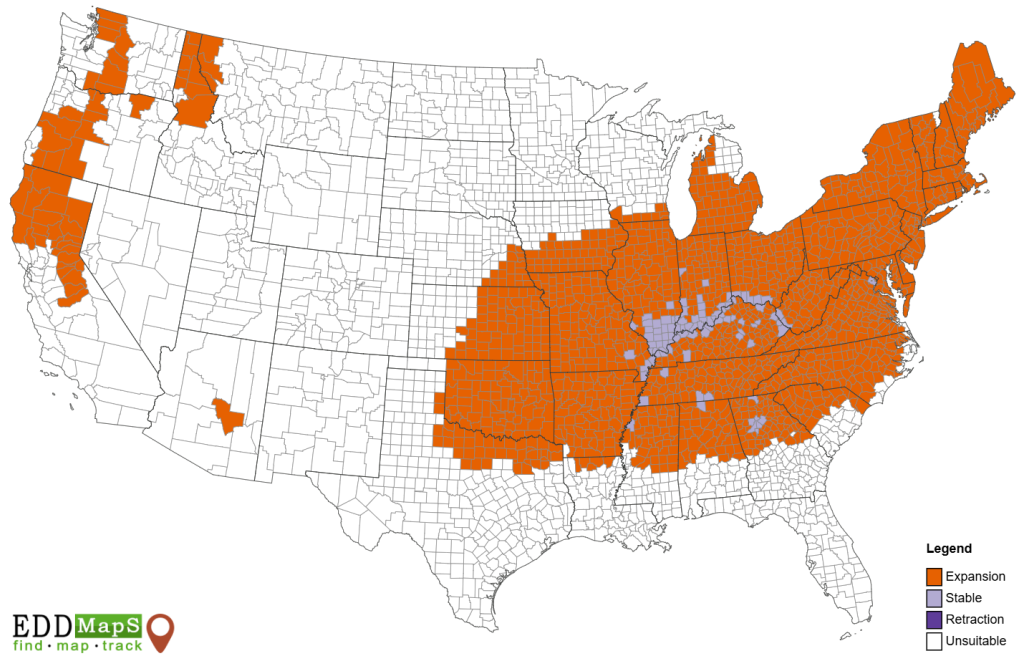

Click the + to expand information about each plant. In the maps below, purple represents the current range of the plant, and orange represents where the plant may spread in the coming decades. Click the image of the map for an interactive version.

Tree-of-heaven

Tree-of-heaven is a rapidly growing tree that can reach up to 80 feet tall, with leaves similar to those of black walnut or staghorn sumac. It grows in open or partly shaded areas (but not full shade) and spreads both by seed and through root suckers that form new trunks. Mid-to-late summer is the best time to apply herbicide to kill its roots.

Callery pear

Callery pear is a small tree up to 40 feet tall with large white flowers that look similar to plum or crabapple flowers—but unlike them, Callery pear flowers have a strong unpleasant smell. Callery pear prefers full sun and can grow along forest edges. It can spread through seeds and roots, so you need to kill or remove the entire root system to effectively suppress it. Bradford pear is a type of Callery pear.

Kudzu

Kudzu is a perennial vine that grows 35 to 100 feet long and can form dense blankets on the ground, in shrubs, and up trees. It thrives in just about any terrestrial habitat but spreads fastest in open areas. Mowing, cutting vines just above ground level, and some herbicides are management options, as long as you kill or remove the entire root system.

Chaff flower

Chaff flower is an herbaceous perennial that grows 3 to 5 feet tall. It prefers bottomlands and areas near streams, but it can thrive in a variety of habitats. Its seeds latch onto clothing and fur very easily, so getting in the habit of removing all plant material from your clothes and your pets is a good way to slow its spread.

Another possibility to be aware of is “sleeper invasives.” These are non-native species that don’t start off as invasive when they first arrive in a new region. They might exist at low population levels for years, then become more common and start causing problems when environmental conditions change in a way that favors them.

What you can do

The most impactful thing you can do in light of changing conditions is to proactively monitor your woods for invasive species like those listed above. Managing a new, small population of an undesired plant is much easier than managing a population that has been growing for years.

Here’s more good news: anything you do to keep your woods healthy will also make it more resilient against invasive species. It’s worthwhile to try to get rid of undesired species, but actively promoting native species in your woods is just as important.

Although invasive plants can take advantage of recently disturbed areas, don’t let that stop you from doing a timber harvest. Creating canopy gaps remains an important way to improve the health of many woodlands—for example, the next generation of light-loving trees like aspens, birches, pines, hickories, and oaks depend on canopy gaps to grow.

When you are planning a timber harvest, ask a forester for advice on how to best encourage native plants and discourage invasive plants in the process. You’ll likely want to spend some time assessing and managing the invasive plants on the site to get their populations as low as possible before the harvest. Then after the harvest, consider seeding native understory plants, and proactively remove any invasive plants that emerge.

Here are two more things you can do to protect your woods:

- When buying plants from a nursery, make sure that they are not considered invasive anywhere in the U.S. (not just Wisconsin).

- If you have friends or family who live south of you, ask them for updates on invasive species trends in their communities. Their experiences could be a preview of what you might encounter in the future—and now is a great time to prepare.

Further Reading

- Climate Change and Invasive Species (North American Invasive Species Management Association, 2022)

- The Future of Midwest Invasive Plants (Midwest Invasive Plant Network)

- Invasive Species Distribution Maps (Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System)

- Bulletin #4: Invasive Species (Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts) (PDF)

- Invasive Species in a Changing Climate (Invasive Species Centre)

- How Climate Change Drives the Spread of Invasive Plants (Columbia University, 2024)

- An Update on Invasive Plant Control (My Wisconsin Woods, 2024)

- Forest Ecosystem Vulnerability Assessment and Synthesis for Northern Wisconsin and Western Upper Michigan (US Forest Service, 2014) (PDF)

Keep learning about…

If you have questions about invasive plants or the changing climate in your woods, or if you have feedback on this webpage, contact:

Keith Phelps

Working Lands Forestry Educator

keith.phelps@wisc.edu

920-840-7504

Scott Hershberger

Forestry Communications Specialist

scott.hershberger@wisc.edu

Page last updated September 2025.

Additional photo credits:

- Tree-of-heaven: Richard Gardner, Bugwood.org

- Japanese barberry: Chris Evans, University of Illinois, Bugwood.org

- Round leaf bittersweet: Leslie J. Mehrhoff, University of Connecticut, Bugwood.org

- Glossy buckthorn: Rob Routledge, Sault College, Bugwood.org

- Callery pear: Leslie J. Mehrhoff, University of Connecticut, Bugwood.org

- Kudzu: Amy Ferriter, State of Idaho, Bugwood.org

- Chaff flower: New York Invasive Species Information